César Chávez

César Chávez

César Chávez speaking at a NFWA meeting, Lamont, ca. 1966. Photo by Emmon Clarke.

Cesario “César” Chávez was born in Yuma Arizona on March 31, 1927. When he was ten, the Chávez family was forced to leave Arizona and they moved to California where they worked in the fields. Right after finishing junior high school, César went to work full-time. In 1946, he enlisted in the Navy. He was honorably discharged and soon after he married Helen Fabela in October 1948. After an attempt to work on timber jobs and moving to Crescent City, César and Helen moved back to San José’s neighborhood Sal Si Puedes (Get Out If You Can).

Fred Ross Sr. standing with César Chávez on stage at Filipino Hall, Delano, September 1, 1966. Photo by John Kouns.

An unidentified man, Bonnie Chatfiled, César Chávez, and Alice Jiménez pose for a photo, Delano, 1966. Photo by Emmon Clarke.

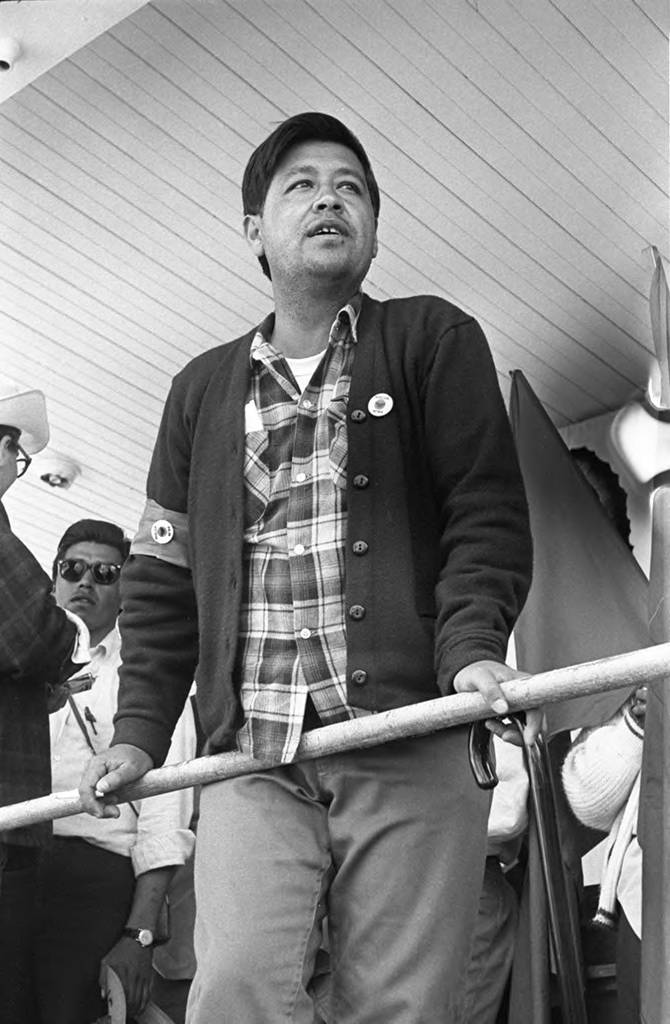

César Chávez leaning on a rail during the march to Sacramento, 1966

Unlike the March on Washington of the Civil Rights era that had a group converged on one place, the pilgrimage to Sacramento chose Mao’s model of a traveling march that organized people along the route. Thus, the march was planned to pass through as many small towns as possible. The march was led by a farmworker carrying a banner of Our Lady of Guadalupe, patron saint of Mexico, made by 22-year-old Alicia Jiménez from Sacramento. American and Mexican flags were also carried at the head of the procession. As the marchers walked single file along Highway 99 and on small roads, people used to come to cheer the workers on and offer food or drinks. Sometimes, music performers welcomed the marchers and a few of these local musicians joined the march to Sacramento. A farmworker advanced team devised strategies to mobilize local farmworker committees and groups to welcome the marchers, feed them, organize a rally each evening and a mass the next morning. At each rally, Luis Valdez proclaimed the “Plan de Delano,” calling for the liberation of the farmworker. The plan was modeled after Emiliano Zapata’s Plan de Ayala. Teatro Campesino also performed during those rallies. The physical suffering of the long march enhanced the religious aspects. “Every step was a needle,” César Chávez recalled. He suffered from a swollen ankle, blisters, and fever for a day or two. Then, he continued the march hobbling a cane. “The penance part of it,” he said, “is the most important thing of the pilgrimage.”

The grape boycott had an important impact because it was used effectively by the abolitionists and the civil rights movement leader, Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. In 1968, César Chávez fasted for 25 days to rededicate the movement to nonviolence. When he broke his fast on March 10, he was joined by thousands of farmworkers and supporters, plus the national press. The guest of honor, U.S. Senator Robert F. Kennedy, called Chavez “one of the heroic figures of our time”.

César Chávez picketing at a Perelli-Minetti grape field, Delano, 1967. Photo by Emmon Clarke.

Senator Robert Kennedy gives César Chávez a piece of bread ending Chávez’s fast. Helen Chávez is seated next to Senator Kennedy, Delano, March 10, 1968. Photo by John Kouns.

After the assassination of King on April 4, 1968, Chávez gave a speech at the Calvary Episcopal Church in Manhattan in May 1968. There he explained how the farmworker struggle was more than a union dispute: “People raise the question: Is this a strike or is it a civil rights fight? In California, in Texas, or in the South, anytime you strike, it becomes a civil rights movement. It becomes a civil rights fight.”

In 1974, a labor law bill written by César Chávez and John F. Henning was introduced by Assemblyman Richard Alatorre. But Governor Ronald Reagan opposed it and killed the Bill. The election of Jerry Brown as governor made it possible for him and César Chávez to agree on a framework and a strategy to pass the legislation. A new bill was introduced on April 9, 1975, by Assemblyman Howard Berman and Senator John Dunlop. Governor Brown negotiated a deal with the UFW, the growers, and the Teamsters on May 5, and he signed the bill on June 5. The act established for the first time the right to collective bargaining for farmworkers in California. Chávez continued as leader of the UFW until he passed away on April 23, 1993. A crowd of approximately 50,000 people attended his funeral service at Forty Acres.

César Chávez claps during a protest against Governor Reagan’s tuition policy, Sacramento, 1967. Photo by Emmon Clarke.

Tom & Ethel Bradley Center

California State University, Northridge

18111 Nordhoff Street, Northridge, CA 91330

Phone: (818) 677-1200 / Contact Us