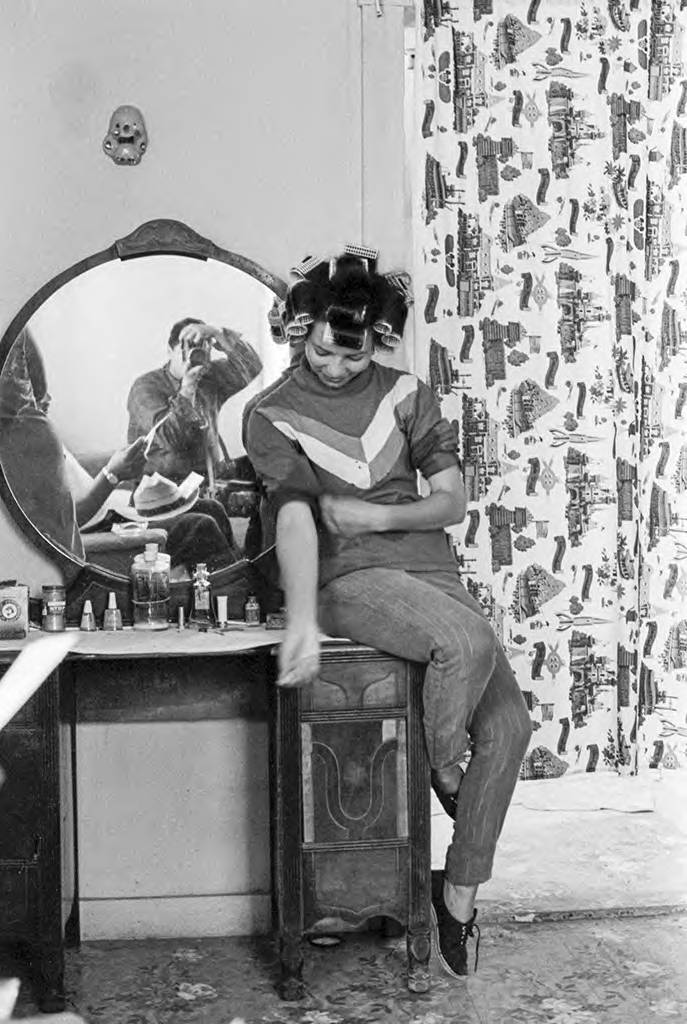

Emmon Clarke

Emmon Clarke

Emmon Clarke working at the office of El Malcriado, Delano, ca. 1966.

Emmon Maika’aloa Clarke (1933–2022) was born in Honolulu, Hawaii, of mixed-race parents—Hawaiian/English. He became interested in photography at an early age inspired by images in the magazines Look, Life, and Saturday Evening Post. “I wanted to be one of those guys,” he said. In 1950, He joined the army two weeks before the Korean War started. Later, he built a career in the military. He married his wife, Judith, in 1962, who persuaded him to move initially to Dinuba, California, where she grew up.

They lived with her parents for a few months until she got a job as a social worker in Tulare County for a year (1963-64), where they saw the emerging farmworker movement. Because of Judith’s work, they moved to Eureka and later to Moran. While they were living there, Emmon decided to visit Delano and explored the possibility of volunteering for the National Farm Workers Association. “I wanted to be part of the movement and use my photography to help,” he recalled.

The staff of the newspaper El Malcriado pose for a group photo in front of Doug Adair’s Econoline Ford Van. Juan Bejarano, Donna Haber, Daniel de los Reyes, Bill Esher, Mary Murphy, Doug Adair, Marcia Brooks, Kerry Ohta, and Emmon Clarke, Delano, 1966.

On his second day as a volunteer, on October 15, 1966, he photographed picketer Manuel Rivera being run over by a truck at the Hourigan-Mosesian-Goldberg Company packing shed in Delano. “I shot it with a 28-millimeter lens. I was running backward, shooting as it all happened,” he told Richard Street in an oral history interview. That event persuaded him to stay and volunteer as a photographer and later photo editor of El Malcriado for seven months. He documented the union’s activities on the picket line, in meetings, at rallies, and in the labor camps of the San Joaquín Valley and briefly in Starr County, Texas. He also photographed picket and fundraising activities in Los Angeles and San Francisco. Clarke documented some early performances of El Teatro Campesino, including one in Berkeley. The reality of the social struggle is revealed in Clarke’s photographs, and in both the recognizable names and unnamed faces, the viewer sees the toil and toll of protest.

According to the U.S. census of 1960, almost one-third of the 3,339 families residing in Starr County had annual incomes of under $1,000. About 70% earned less than $3,000, which was the cut-off level for defining the poverty-stricken when the “War on Poverty” was launched in 1964. The average per capita income in 1960 was $534, making Starr County the most impoverished county in Texas. Half of mostly Mexican American homes in the Valley had neither hot water nor plumbing and the average farmworker was a Mexican American who had 6 years of schooling. Diseases like typhoid, typhus, dysentery, and leprosy were common. Strikers in South Texas were having a harder time than in California. Not only their wages, working, and living conditions were worse than for California farmworkers, but the growers’ and the authorities’ opposition to the strikers was stronger

Emmon Clarke Speaks About His Work

Tom & Ethel Bradley Center

California State University, Northridge

18111 Nordhoff Street, Northridge, CA 91330

Phone: (818) 677-1200 / Contact Us